Bash (Bourne Again SHell) is the most widely used shell and command language interpreter for Linux systems. It acts as a command-line interface where users can execute commands, run scripts, and automate tasks.

Understanding Bash fundamentals and how to configure the Bash environment is essential for Linux developers and system administrators to work efficiently, customize their workflow, and harness the full power of the Linux shell.

Bash Basics

Bash is a command interpreter: it reads commands entered interactively or from scripts and executes them. Originally designed as a free replacement for the Bourne Shell (sh), Bash supports scripting, variables, loops, conditionals, and functions.

It is the default shell on most Linux distributions and macOS terminals. Bash supports command history, job control, auto-completion, and programmable prompts.

Bash Startup and Configuration Files

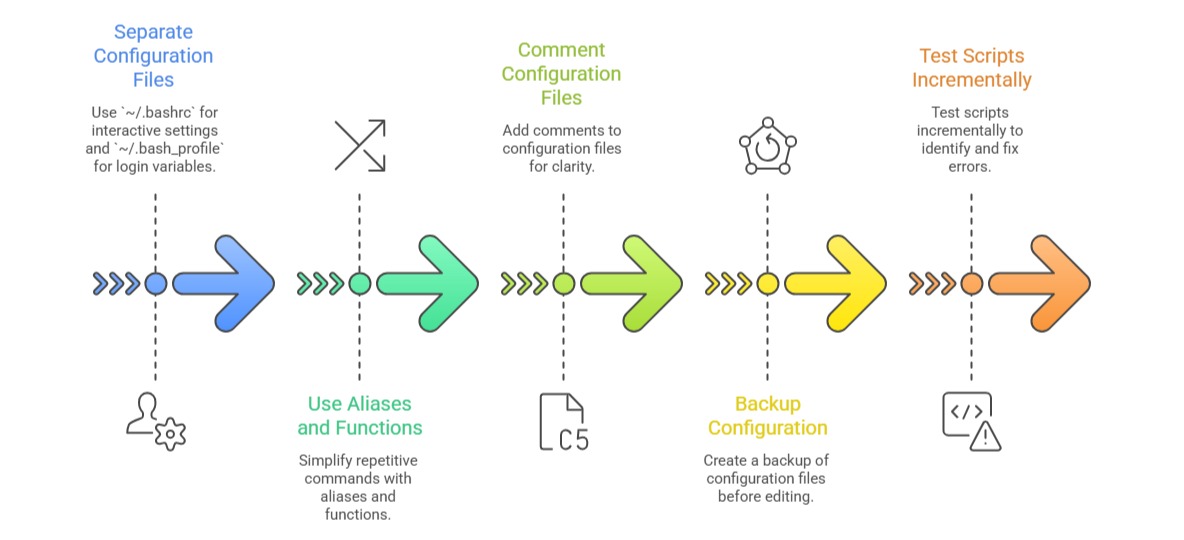

Bash reads several configuration files during startup, which control the environment and behavior:

1. System-Wide Files (applied to all users)

/etc/profile: executed for login shells.

Files in /etc/profile.d/: additional scripts loaded by /etc/profile.

/etc/bash.bashrc: sometimes sourced for interactive non-login shells.

2. User-Specific Files (loaded from the home directory)

~/.bash_profile or ~/.bash_login or ~/.profile: read for login shells, in this order, stopping after the first found.

~/.bashrc: read for interactive non-login shells (for example, when opening a terminal emulator).

~/.bash_logout: executed when login shell exits.

Best practice involves placing environment variables and export commands in ~/.bash_profile and interactive shell configurations (aliases, functions, command prompts) in ~/.bashrc. It is common to source ~/.bashrc from ~/.bash_profile to unify configurations.

Example .bash_profile snippet:

if [ -f ~/.bashrc ]; then

. ~/.bashrc

fiEnvironment Variables

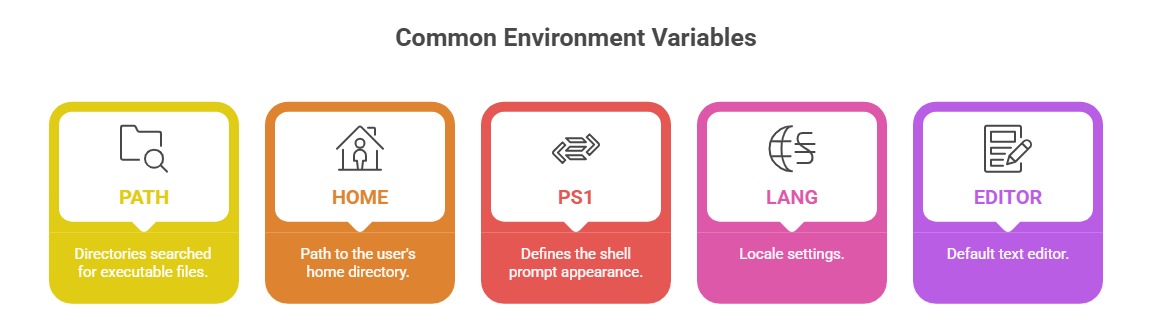

Environment variables are key-value pairs that influence the behavior of the shell and applications. Bash reads them during initialization and allows users to set or modify them.

Setting environment variables:

export VARIABLE_NAME="value"For example:

export PATH="$HOME/bin:$PATH"This prepends a custom bin directory to the executable search path.

Bash Aliases and Functions

Aliases are shortcuts for long or frequently used commands, improving command efficiency.

Defining an alias:

alias ll='ls -alF'The example defines ll as a detailed listing alternative to ls.

Functions allow defining reusable blocks of code with parameters:

Example function:

function mkcd() {

mkdir -p "$1"

cd "$1"

}This creates a directory and changes into it in one command (mkcd dirname).

Scripting Basics

Bash scripts are plain text files containing sequences of commands executed by Bash.

Key scripting principles:

1. Use a shebang line at the start:

#!/bin/bash2. Scripts must be made executable:

chmod +x script.sh3. Variables:

name="Linux"

echo "Hello, $name"4. Control structures: if-else, case, loops (for, while).

5. Comments start with #.

Example script snippet:

#!/bin/bash

if [ -d "$1" ]; then

echo "Directory exists."

else

echo "Directory not found."

fi

Prompt Customization (PS1)

The PS1 variable controls the terminal prompt format. It can include dynamic information:

\u - username.

\h - hostname.

\w - current working directory.

Colors can be added using ANSI escape sequences.

Example:

PS1="\[\e[32m\]\u@\h \w \$\[\e[m\] "This displays the username@hostname in green followed by the working directory.

Best Practices for Bash Configuration

Class Sessions

Sales Campaign

We have a sales campaign on our promoted courses and products. You can purchase 1 products at a discounted price up to 15% discount.